On June 25, 1876, Alexander Graham Bell demonstrated the prototype of its new invention, the telephone and it is this apparatus that I’m talking about today.

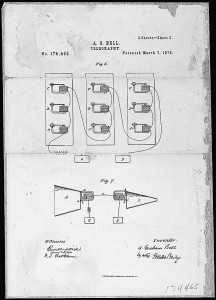

We are not going into a controversy of who actually invented the telephone and the reasons why Antonio Meucci (who had begun the process of its patent years earlier) and Elisha Gray failed to patent it before. The fact is that the patent was issued to Bell on March 7, 1876.

Bell had great knowledge of acoustics and voice modulation as his mother and wife were deaf, and his father, grandfather and uncle were all elocutionists.

For many years he focused his efforts in trying to transmit sound through electric means.

In 1874 while trying to develop a harmonic telegraph, his assistant Thomas A. Watson discovered that could transmit more than one note using iron membranes driven by electromagnets. Bell immediately saw the possibilities it offered them and began to develop a new device to transmit voice.

In 1875 they built the first model (shown in the photo at left) that did not really work.

After some experiments and modifications, including a membrane of little harder iron, or a liquid transmitter, Bell decided to patent it (even without many details of the invention) seeing that it was viable (with quite discreet results).

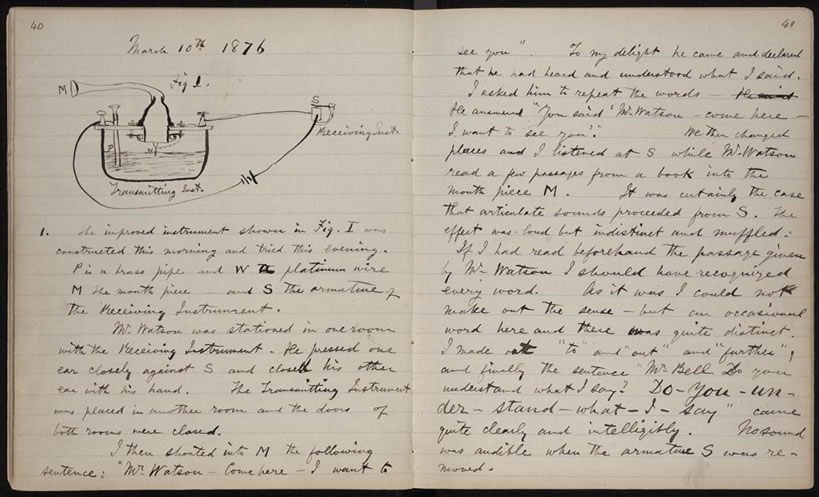

On March 7, 1876 he was awarded with the patent and starts experimenting again. Only three days later, on March 10, managed to transmit the first words to his assistant who were in another room.

This page in his laboratory notebook records the event:

Diario de laboratorio de Graham Bell. Dia 10 de Marzo de 1876.

Diario de laboratorio de Graham Bell. Dia 10 de Marzo de 1876.

“I then shouted into M [the mouthpiece] the following sentence: ‘Mr. Watson–come here–I want to see you.’ To my delight he came and declared that he had heard and understood what I said. “.

The demonstration that took place in the Universal Exhibition in Philadelphia, announced the invention to the world and the news caught the press at the time.

In November 26, 1876 the first telephone conversation between the cities of Boston and Salem, Massachusetts, at a distance of 16 miles is performed.

One of the two phones that were used at that time is in the National Museum of American History (Smithsonian).

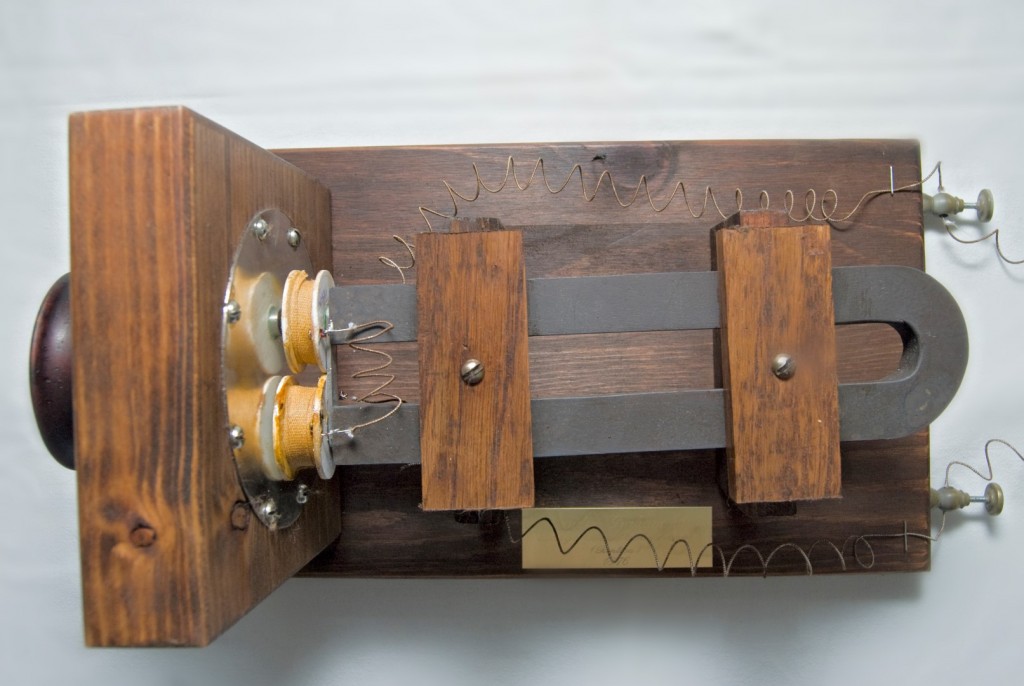

It consisted of an iron diaphragm, two iron core coils and a permanent horseshoe magnet.

As described by the museum itself:

“When used as a transmitter, sound waves at the mouthpiece cause the diaphragm to move, inducing a fluctuating current in the electromagnets. This current is conducted over wires to a similar instrument, acting as a receiver. There, the fluctuating current in the electromagnets causes the diaphragm to move, producing air vibrations that can be heard by the ear. This was a marginal arrangement, but it worked well enough to be employed in the first commercial services in 1877. The magneto receiver continued to be used, but the transmitters were soon replaced by a carbon variable-resistance device designed by Francis Blake and based on a principle patented by Thomas Edison.”

And this is where we present our work.

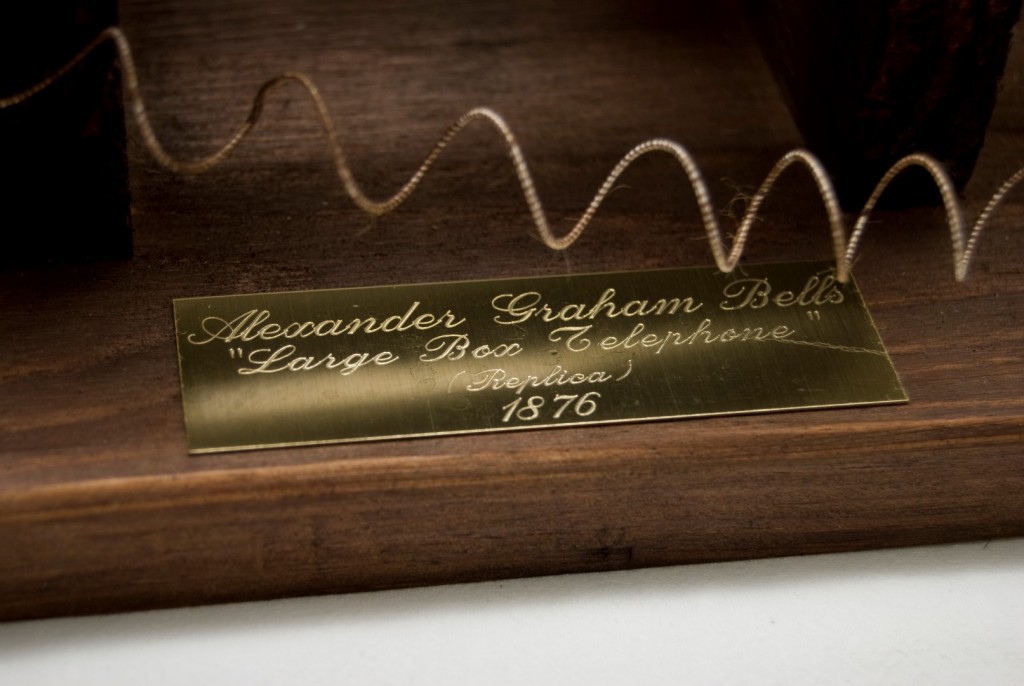

With the invaluable assistance of my father (Jose Manuel Corral Rodriguez), who has developed and built with us this model (and here we thank him), we have built a working replica of the first commercial model.

Although some elements have been modified to replace by modern pieces (like magnets), the external appearance is the same as the original.

Here’s a soundcheck:

As explained in the description of the Smithsonian, soon using this model as a transmitter and receiver, they decided to adopt the carbon microphone, thanks to which they could hear much better.

We have also constructed a (not replica) device to use one of these microphones without the need to have two copies of the phone.

Together with some 32 feet cable, to be able to move away enough so that you can hear the device itself, not the raw voice.

You can buy one of our replicas in our store.

Leave a Reply